John and Brigetta were pastors of neighboring congregations. Even though they represented different denominations, their congregations were quite similar. Both had approximately 110 members attending Sunday worship, and both congregations had been stuck at that number for the past eight years. John and Brigetta knew each other well, as they belonged to the same clergy support group, yet their leadership styles differed greatly.

Brigetta was a tough-thinking woman who made most of the decisions at Good Samaritan Church. She had a strong, driven, Type-A personality. Brigetta had a clear vision of where the congregation should be headed, and she worked tirelessly at getting laypeople to carry out her vision. Although she had great ideas, she continually encountered lackluster support for these proposals from the board and committee members. Some lay leaders had tried to revise some of her ideas to make them more relevant to congregational needs, but she insisted on their doing things her way. Brigetta repeatedly rebuffed their attempts to gain some ownership of her plans by incorporating some of their own, and in the end, they acquiesced to her. Over time, members who had leadership capacities simply stopped serving on congregational boards and committees. Brigetta had not noticed that lay leaders lacked enthusiasm because they felt they were treated as lackeys whose purpose was to carry out her vision. She, on the other hand, complained to her colleagues that she wished she had just a few capable lay leaders who wanted to do something to make the congregation thrive.

John was laid-back and easygoing. He also had a natural proclivity to pursue peace at all costs. Early in his tenure at St. John’s, he had tried exercising leadership but had found himself quickly overruled by strong-willed lay leaders who disagreed with the changes he wanted to make. After several attempts with the same results, he decided to offer the congregation excellent pastoral care and leave the leadership of the congregation in the hands of the strong lay leaders. He saw himself as carrying out the directions his lay leaders set for him, and he seemed willing to pay this price to keep the peace. Besides, these lay leaders were an intimidating bunch. They were tough, successful executives in their corporate settings, and in their opinion John knew little about either leadership or management. Sometimes he knew that what they were proposing would not work, because he was in touch with a much broader segment of the congregation. But he would bite his tongue and go along with their proposals, though his heart was not in them, and he gave only token support to implementing their ideas.

The Polarity to Be Managed

Here were two congregations going nowhere. In each case, there was no partnership between clergy and lay leaders. The congregations were stuck on alternate poles of this polarity, and both were experiencing more and more of the downside of their respective poles.

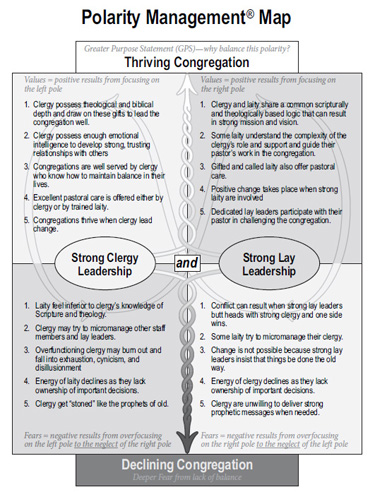

A polarity is a pair of truths that are interdependent. Neither truth stands alone. They complement each other. Congregations often find themselves in power struggles over the two poles of a polarity. Both sides believe strongly that they are right. People on each side assume that if they are right, their opponents must be wrong—classic “either/or” thinking. Either we are right or they are right—and we know we are right! When people argue about the two truths, both sides will be right, and they will need each other to experience the whole truth.

Let’s take a look at each quadrant in the “Strong Clergy Leadership and Strong Lay Leadership” polarity in detail:

The Upside of Strong Clergy Leadership

- Clergy possess theological and biblical depth and draw on those gifts to lead the congregation well

- Clergy possess enough emotional intelligence to develop strong, trusting relationships with others

- Congregations are well served by clergy who know how to maintain balance in their lives

- Excellent pastoral care is offered

- Congregations thrive when clergy lead congregational change

- Strong prophetic messages are delivered when necessary

The Upside of Strong Lay Leadership

- Clergy and laity share a common scripturally and theologically based logic that can result in strong mission and vision

- Some laity understand the complexity of the clergy’s role and support and guide their pastor’s work in the congregation

- Gifted and called laity also offer pastoral care

- Positive change takes place in a congregation when strong lay leaders are involved

- Dedicated lay leaders participate with their pastor in challenging the congregation

The Downside of Strong Clergy Leadership

- Some laity may feel inferior to clergy in their knowledge of scripture, theology, and congregational life

- Clergy may try to micromanage other staff members and lay leaders

- Overfunctioning clergy may burn out and fall into exhaustion, cynicism, and disillusionment

- Lay leaders’ energy declines because they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are, so to speak, stoned to death like the prophets of old

The Downside of Strong Lay Leadership

- Conflict can result when strong lay leaders butt heads with strong clergy, and one side wins

- Some laity try to micromanage their clergy

- Change is not possible because strong lay leaders insist that things be done the old way

- The energy of clergy declines as they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are unwilling to deliver strong, prophetic messages

Thriving congregations have found ways to empower their clergy and to empower their laity. It is important to do both. One way is to reproduce this polarity on a

single sheet of paper and ask for an hour’s discussion at the next board meeting. The question that needs to be asked at such a time is this: “Are we managing this polarity well or managing it poorly?” If there is consensus that the congregation is managing it poorly, the board can ask for suggestions of action steps that might bring the two poles into better balance. If the suggestions are not particularly robust, a task force can be appointed to study the polarity and bring recommendations. Managing this polarity is worth that expenditure of energy.

__________________________________________________________

Adapted from Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson, copyright © 2010 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

__________________________________________________________

Comment on this article on the Alban Roundtable blog

FEATURED RESOURCES

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities

by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson

A polarity is a pair of truths that need each other over time. When an argument is about two poles of a polarity, both sides are right and need each other to experience the whole truth. This phenomenon has been recognized and written about for centuries in philosophy and religion, and the research is clear: leaders and organizations that manage polarities well outperform those who don’t.

Leadership in Congregations

Leadership in Congregations

Edited by Richard Bass

This book gathers the collected wisdom of more than ten years of Alban research and reflection on what it means to be a leader in a congregation, how our perceptions of leadership are changing, and exciting new directions for leadership in the future. With pieces by diverse church leaders, this volume gathers in one place a variety of essays that approach the leadership task and challenge with insight, depth, humor, and imagination.

Choosing Partnership, Sharing Ministry: A Vision for New Spiritual Community

Choosing Partnership, Sharing Ministry: A Vision for New Spiritual Community

by Marcia Barnes Bailey

Partnership invites us on a journey that can transform us as leaders, as human beings, and as the church. Bailey invites pastors and congregations to a new understanding of ministry, leadership, and the church that challenges hierarchy by fully sharing responsibilities, risks, and rewards in mutual ministry. Partnership unleashes the Spirit to create a new vision and reality among us, moving us one step closer to living into God’s reign.

The Spirit-Led Leader: Nine Leadership Practices and Soul Principles

The Spirit-Led Leader: Nine Leadership Practices and Soul Principles

by Timothy C. Geoffrion

Designed for pastors, executives, administrators, managers, coordinators, and all who see themselves as leaders and who want to fulfill their God-given purpose, The Spirit-Led Leader addresses the critical fusion of spiritual life and leadership for those who not only want to see results but also desire to care just as deeply about who they are and how they lead as they do about what they produce and accomplish. Geoffrion creates a new vision for spiritual leadership as partly an art, partly a result of careful planning, and always a working of the grace of God.

__________________________________________________________

Copyright © 2010, the Alban Institute. All rights reserved. We encourage you to share articles from the Alban Weekly with your congregation. We gladly allow permission to reprint articles from the Alban Weekly for one-time use by congregations and their leaders when the material is offered free of charge. All we ask is that you write to us at alban@div.duke.edu and let us know how the Alban Weekly is making an impact in your congregation. If you would like to use any other Alban material, or if your intended use of the Alban Weekly does not fall within this scope, please submit our reprint permission request form.

Subscribe to the

Archive of past issues of the Alban Weekly.