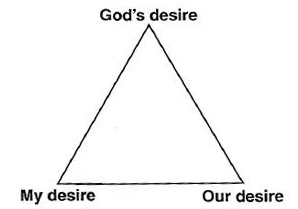

We believe in a God to whom “all hearts are open, all desires known.” Sometimes we have a lot of work to do—uncovering the desires of our own hearts—before we can hear clearly what God may desire for us. An incarnational spirituality requires that we engage in prayerful dialogue with our own longings. As you ponder your congregation’s call regarding size and numerical growth, you may find it helpful to map out the yearnings that are imbedded in this choice.

At all three points on the map, the Spirit of God is working. All of our individual desires, if we trace them back far enough, are rooted in the goodness of creation and oriented toward union with God. To be sure, they become distorted. What once was called idolatry is now more commonly called addiction: placing something essentially good (food, drink, sex, money, work, approval) at the very center of our lives. Whenever we try to fill the “God-shaped hole” in our being with something other than God, we confuse the giver with the gift, investing ultimate trust in persons or things too fragile to bear that weight. Even so, each longing is rooted in the subsoil of our God-given humanness.

As a congregation wrestles with the possibility of growth, it is important to create space where leaders and members can explore their own particular desires in this matter and recognize the conflicts that exist even within themselves. Clergy can have an especially tough time admitting their own resistance to growth. It is much easier to project ambivalence on others—pinning the problem on parish old-timers, on the denomination’s mistakes or on the attitudes of the next generation. There are plenty of reasons a pastor might dread the spiritual and political demands of a size transition.

A congregation approaching size decisions needs many safe settings—over a period of months and years—for members and leaders to ponder the voices they hear in their own hearts and minds. Quiet days, study groups, and workshops with leaders from other congregations can help. By whatever means may fit your context, ask people to trace their own longings back to the very deepest desires of their hearts. As leaders and members begin to inhabit their personal desires and to share these openly with others, they may be ready to recognize the conflicting voices resonating within the congregation’s corporate personality. What do we desire together? This question cannot be answered through the mathematics of a vote or survey, although there may come a point, after much conversation and prayer, when testing the waters with a survey or poll will be a clarifying step. We have a communal relationship with God that both embodies and transcends all our individual faith journeys. At this corner of the triangle, we are challenged to accept that the ambivalence belongs to us together, even though different segments of the community may vocalize particular strands of the conversation.

When a congregation changes size, its culture and style will also change to some extent, and these are not simple matters. Sometimes we talk about sticking to the gospel and not letting “mere” matters of culture and style get in the way. Style is not a peripheral matter. There is no generic, culture-free Christianity. Every revelation of spiritual truth is embedded in a specific context, and every expression of faith has a distinctive style. Even the bedrock proclamation of Christian faith—the gospel—is plural in context and style. Though Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John all strive to express the central news, each uses the idiom of a particular cultural setting and each conveys religious meaning in a characteristic style. Add Paul to the mix; add the early church’s matriarchs and patriarchs; add the witnesses of faith down through the centuries—nowhere will we find a generic faith that can be separated absolutely from its cultural context and expressive style. So, if we are to clarify what we together desire, it helps to explore the deeply significant context and style in which the faith of this congregation has been formed.

Once we come to recognize the sources of our congregation’s unique character and aspirations, we will be faced with the offer—and challenge—of transformation. Though God has been active in the formation of “my desire” and “our desire,” the third corner of the triangle never collapses into the other two. The transcendent One maintains a holy otherness; the living God has something new to say to us and to the world. This is the place for the distinctive task of communal discernment, by which I mean the processes different traditions have employed through the ages as they have grappled with the third corner of the triangle.

One powerful way we can listen for the voice of “God as Other” is to contemplate the “other” who is nearer at hand. This might occur informally through attentive neighborhood walks and quiet conversations. It might also take the form of a more structured demographic study, supplemented by interviews with a spectrum of community leaders. However it occurs, such an effort only bears spiritual fruit to the extent that we open ourselves to the otherness of our neighbors, allowing the stories of their lives to break through our self-absorption. Community statistics cannot answer for you the question of your church’s vocation in its particular place and time. But a careful exploration of community realities will stimulate holy imagination and break open new questions about your congregation’s potential role in people’s lives.

Now comes the moment when we try to step away from the bottom of the “desire triangle,” when we try to feel the heat of God’s desire for us and for the people around us. Ask yourselves, “Who in this community is God trying to reach?” This isn’t a one-time question, a step in a mechanical process. Rather, it is a stance you can practice until it begins to feel more natural to the parish personality. Who is God especially concerned about in your community? “Everyone” is a true but inadequate answer.

We may resist asking whom God is seeking because we are afraid of becoming overwhelmed, buried in a level of responsibility we cannot possibly bear. If you experience that fear, notice it. Name it. Most of all, offer it back to God in prayer. Our prayers at moments like this don’t have to be polite. When Moses had some complaints of his own about unbearable responsibility, and he put these complaints bluntly before God, God’s response to this loud objection is generous and practical—God spreads out the spirit onto 70 additional leaders. Your congregation is not the only vehicle of God’s caring; you can survive the heat of God’s desire if you ask for the help that you need.

Comment on this article at the Alban Roundtable blog.

__________________________________________________________

Adapted from The In-Between Church: Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations by Alice Mann, copyright © 1998 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

__________________________________________________________

FEATURED RESOURCES

The In-Between Church: Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations

The In-Between Church: Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations

by Alice Mann

Alice Mann draws on her lengthy experience in helping congregations deal with the hurdles and anxieties of expansion or contraction in size. Often, congregations experiencing size change do not recognize the need to change culture and form as part of the successful adaptation process. Mann details the adjustments in attitude—as well as practice—that are necessary to support successful size change.

Raising the Roof: The Pastoral-to-Program Size Transition

Raising the Roof: The Pastoral-to-Program Size Transition

by Alice Mann

Pastoral-to-program size change is frequently described as the most challenging of growth transitions for congregations. Alban senior consultant Alice Mann, author of The In-Between Church: Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations, addresses the difficulties of that transition in this resource designed specifically for a congregational learning team.

Can Our Church Live? Redeveloping Congregations in Decline

Can Our Church Live? Redeveloping Congregations in Decline

by Alice Mann

Nothing on earth lives forever—not even congregations. Alban Institute senior consultant Alice Mann explains how the natural life cycle of a congregation, as well as other internal and external factors, can produce a congregation that is in real trouble. She then offers hope for congregations that want to change. Practical options for congregations, leadership challenges for laity and clergy, and ways to work with denominations are detailed, and engaging discussion questions provide a basis for congregational planning.

Size Transitions in Congregations

Size Transitions in Congregations

Edited by Beth Ann Gaede

Congregations that seek growth are often frustrated at hitting a plateau—caught in a transition zone between sizes. The Alban Institute has long been recognized as a leader in size transition research and learning, and this anthology offers an in-depth collection of resources, through new articles developed for the book as well as previously published and highly regarded pieces that inform and provoke.

__________________________________________________________

Copyright © 2010, the Alban Institute. All rights reserved. We encourage you to share articles from the Alban Weekly with your congregation. We gladly allow permission to reprint articles from the Alban Weekly for one-time use by congregations and their leaders when the material is offered free of charge. All we ask is that you write to us at alban@div.duke.edu and let us know how the Alban Weekly is making an impact in your congregation. If you would like to use any other Alban material, or if your intended use of the Alban Weekly does not fall within this scope, please submit our reprint permission request form.

Subscribe to the Alban Weekly.

Archive of past issues of the Alban Weekly.