A key annual event is the board’s planning retreat. The senior clergy leader always participates, and depending on the planning focus in a given year, the board invites others to participate as well. The retreat agenda includes devotions and socializing; time for thoughtful and expansive conversation; and also time for practical work, like orienting newcomers and divvying up tasks and roles.

As always with retreats, the ideal is to meet away from usual haunts — somewhere where, if the phone rings, it’s not for you. For the same reason, a clear agreement to limit cell-phone use is a good idea. Staying overnight helps separate the retreat from daily work and fosters flexibility of thinking. These benefits are hard to imagine ahead of time, but they make a big difference. As a retreat facilitator, I have often heard board members say, “I voted against spending the money to meet off-site. But I was wrong. This retreat will pay for itself many times over.”

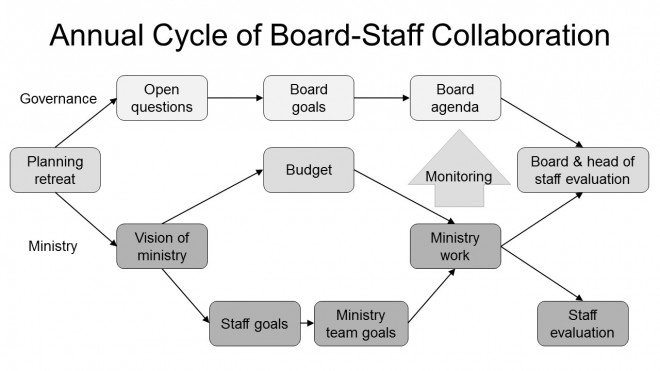

At the retreat, the board creates two major products: a set of open questions about the congregation’s future and an annual vision of ministry. Both are official actions of the board. Both take the form of lists — a list of future-oriented questions and a list of goals for the coming year or so. Both lists are short — ideally, no more than three items apiece.

Why so short? Because congregations suffer from attention deficit disorder; two or three questions are the most they can hold in their collective sights at once. And the list of priorities in the annual vision of ministry has to be short because, when a list of priorities gets long, it is no longer a list of priorities!

Responsibility for work on open questions belongs to the board, and responsibility for accomplishing the annual vision is owned by the staff, but neither works in isolation. The diagram above highlights four key points of connection between governance and ministry: the annual retreat, the budget process, board monitoring of staff activity, and the annual evaluation of the board and head of staff. These are not, of course, the only moments when the board and staff connect; there are many others. To take a few obvious examples, the clergy leader normally attends board meetings, and sometimes other staff do so as well. Board members participate as volunteers in ministry activities. And as the board adopts, reviews, and modifies its policies on staff activity, board members seek assistance from the staff members who are most familiar with specific pieces of the work.