Pastors Jill Buhler and Jack Smothers moved to new program-size congregations—that is, churches with 150–350 average worship attendance—at about the same time. Both congregations had been slowly declining over the previous ten years. Jill planned to apply a recommendation she had heard that for the first nine to twelve months, her job as pastor was to be a historian and a lover—to get to know people, to find something to love in everybody, and to learn about the congregation’s history as a way of trying to understand its personality. Certain leaders of the congregation became impatient with her. The congregation was losing members, and people wanted to know what she was going to do to help them grow again. She held her ground and insisted that she would soon get to that task, but first she wanted to explore the congregation as an organism and to get to know its people. These leaders cut her some slack and stayed off her case for the first year.

Trouble began brewing, however, when after eighteen months Jill still had not begun to explore ways the congregation might become stronger and more vibrant. During this time she had gotten to know many of the longtime members and learned that they valued their rich tradition and the stability the congregation had enjoyed over the years. Every time she thought of ways the congregation might grow, she felt a lump in her throat, because she knew that the strategy would upset some of the people she had come to know and love. At the end of twenty-four months, when Jill had still not initiated any changes, board members went to their regional executive to see about having her removed.

Jack Smothers, on the other hand, had heard somewhere that if a pastor is going to make any changes, he should do so within the first six months. A new pastor who waits longer than that may not succeed in making changes. For years, the congregation had had only one worship service, with Sunday school at 9:00 am and a traditional service at 10:15, followed by a coffee time. Within three months of arriving, Jack had persuaded the board that if the congregation wanted to grow, it would have to change its Sunday morning schedule to include a traditional service at 8:30 am, Sunday school classes at 9:45, and a contemporary service at 11:00. The congregation went along with these changes for a while. Some longtime members who loved the traditional service began to complain about having to get up so early, and attendance began to slump. The contemporary service had not really gotten off the ground because its leaders did not take time to plan it well. They did not identify a target audience for the service or plan how they would let that target audience know about the new worship service. Within two years, the grumbling and complaining had become so fierce and constant that the governing board went to the denomination’s regional executive to have Jack removed as pastor.

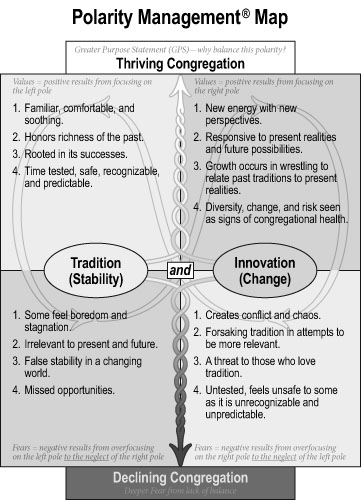

In each of these cases, the new pastor was attending to something important. Jill was paying attention to Tradition, including the need for stability. Jack was paying attention to Innovation, including the need for change. Each got into trouble by not seeing the underlying polarity and by over-focusing on one pole without giving adequate attention to the other pole.

A polarity is a pair of truths that are interdependent. Neither truth stands alone. They complement each other. Congregations often find themselves in power struggles over the two poles of a polarity. Both sides believe strongly that they are right. People on each side assume that if they are right, their opponents must be wrong—classic “either/or” thinking. Either we are right or they are right—and we know we are right!

Many religious systems are good at preserving their core ideology. In the corporate world, the average life of a company is about forty years, and a one-hundred-year-old company is impressive for its staying power. In the church, many faith communities are hundreds of years old; their longevity would indicate that they have managed this polarity well. None of these congregations would be around today if they hadn’t. We believe, however, that it is more challenging to manage the “Tradition and Innovation” polarity well in the twenty-first century than it was in earlier years.

Let’s take a look at each quadrant in the “Tradition and Innovation” polarity in detail:

The Upside of Tradition

A congregation that enjoys the upside of Tradition: feels familiar, comfortable, and soothing; honors the richness of the past; is rooted in its successes; is time tested, safe, recognizable, and predictable.

The Upside of Innovation

A congregation that enjoys the upside of Innovation: brings new energy with new perspectives; responds to present realities and future possibilities; struggles to relate past tradition to present realities; sees diversity, change, and risk as signs of congregational heath.

The Downside of Tradition

The downside of Tradition causes some to feel bored and stagnant; is being out of touch with the present and future; gives rise to false security in a changing world; leads to missed opportunities.

The Downside of Innovation

The downside of Innovation can create conflict and chaos; forsakes tradition in attempts to be more relevant; threatens those who love tradition; feels unsafe to some as it is unrecognizable and unpredictable.

The more we value the upside of one pole, the more we will fear the downside of the opposite pole. The potency of the value and the fear is the same. If we value the upside of one pole at nine on a ten-point scale, we will fear its loss at nine on a ten-point scale. The more people value the upside of one pole, the more they will denigrate the opposite pole by pointing out why it is a bad idea and adding more items to the downside of that pole. So, for example, the more a congregation values the upside of Tradition (feels familiar, comfortable, and soothing), the more it will fear the downside of Innovation (can create conflict and chaos).

If we mistakenly think that only one pole can be adopted (either/or thinking) and hold strong values and fears, as above, we will find it difficult to embrace the other point of view, fearing that we must let go of something we value dearly.

A polarity is managed well when a congregation is maximizing both upsides through action steps and minimizing both downsides through early warnings. Thriving congregations manage to support both Tradition AND Innovation. If they pursue action steps and heed early warnings, the inherent tension between the two poles becomes a virtuous circle in which Tradition becomes a platform for Innovation, and Innovation helps sustain Tradition. Doing this well helps congregations thrive, even if they have never heard of Polarity Management.

__________________________________________________________

Adapted from Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson, copyright © 2010 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

__________________________________________________________

Comment on this article on the Alban Roundtable blog

FEATURED RESOURCES

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities

by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson

A polarity is a pair of truths that need each other over time. When an argument is about two poles of a polarity, both sides are right and need each other to experience the whole truth. This phenomenon has been recognized and written about for centuries in philosophy and religion, and the research is clear: leaders and organizations that manage polarities well outperform those who don’t.

Creating the Future Together: Methods to Inspire Your Whole Faith Community

Creating the Future Together: Methods to Inspire Your Whole Faith Community

by Loren B. Mead and Billie T. Alban

Congregations today face a multitude of challenges in trying to adapt to a quickly changing world. Balancing new concerns with core values is a complicated process that can leave too many members feeling that their voices and needs are not being met. Creating the Future Together explains how congregations can use large group methods to navigate these new waters. This book is designed to familiarize leaders with these whole-system approaches and to provide a conceptual framework for evaluating their potential usefulness against any given challenge.

The Hidden Lives of Congregations: Understanding Church Dynamics

The Hidden Lives of Congregations: Understanding Church Dynamics

by Israel Galindo

Christian educator and consultant Israel Galindo takes leaders below the surface of congregational life to provide a comprehensive, holistic look at the corporate nature of church relationships and the invisible dynamics at play. Informed by family systems theory and grounded in a wide-ranging ecclesiological understanding, Galindo unpacks the factors of congregational lifespan, size, spirituality, and identity and shows how these work together to form the congregation’s hidden life.

Never Call Them Jerks: Healthy Responses to Difficult Behavior

Never Call Them Jerks: Healthy Responses to Difficult Behavior

by Arthur Paul Boers

No church is immune to the problems that can arise when parishioners behave in difficult ways. Responding to such situations with self-awareness and in a manner true to one’s faith tradition makes the difference between peace and disaster. In this must-read book, Boers shows how a better understanding of difficult behavior can help congregational leaders avoid the trap of labeling such parishioners and exercise self-care when the going gets rough.

Strategic Leadership for a Change: Facing Our Losses, Finding Our Future

Strategic Leadership for a Change: Facing Our Losses, Finding Our Future

by Kenneth J. McFayden

Strategic Leadership for a Change provides congregational leaders with new insights and tools for understanding the relationships among change, attachment, loss, and grief. It also helps leaders facilitate the process of grieving, comprehend the centrality of vision, and demonstrate theological reflection in the midst of change, loss, grief, and attaching anew. All this occurs as the congregation aligns its vision with God’s and understands processes of change as processes of fulfillment.

__________________________________________________________

Copyright © 2009, the Alban Institute. All rights reserved. We encourage you to share articles from the Alban Weekly with your congregation. We gladly allow permission to reprint articles from the Alban Weekly for one-time use by congregations and their leaders when the material is offered free of charge. All we ask is that you write to us at alban@div.duke.edu and let us know how the Alban Weekly is making an impact in your congregation. If you would like to use any other Alban material, or if your intended use of the Alban Weekly does not fall within this scope, please submit our reprint permission request form.

Subscribe to the Alban Weekly.

Archive of past issues of the Alban Weekly.